I was looking at a Chagall book with three-year-old Polina, and we

stumbled upon a painting in which the trees grow sideways. She said,

mommy, turn the album. [show more]I did, but then the trees on the other side

started to grow upside down. "I guess," said Polina after some

thought, "he wanted to make it funny."

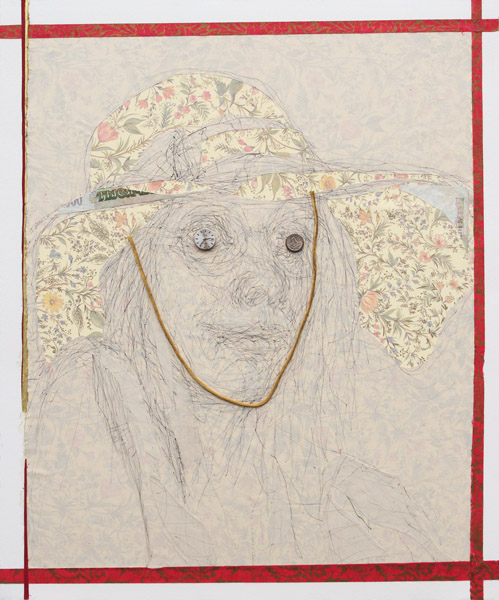

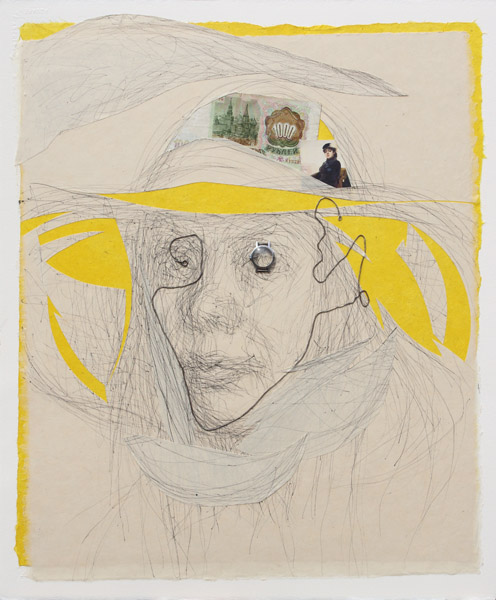

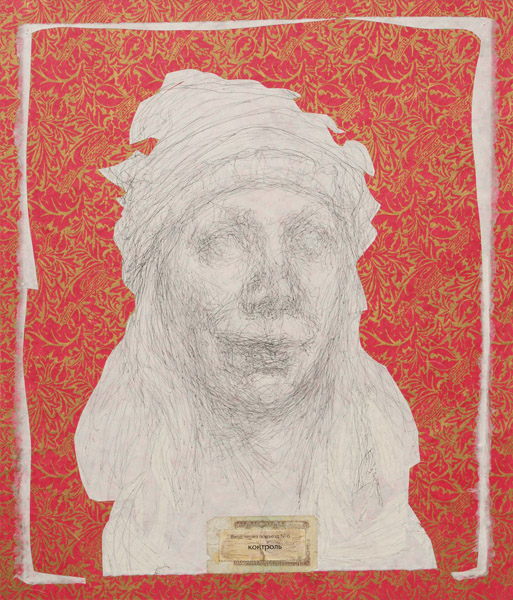

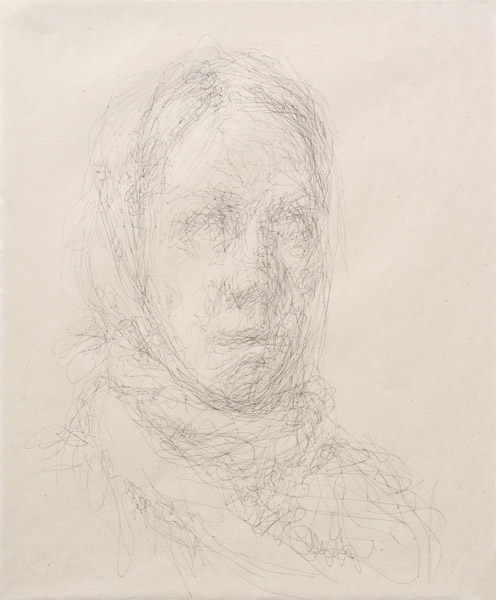

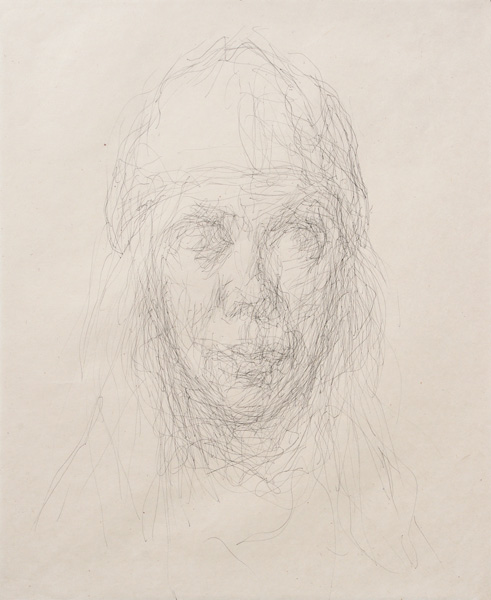

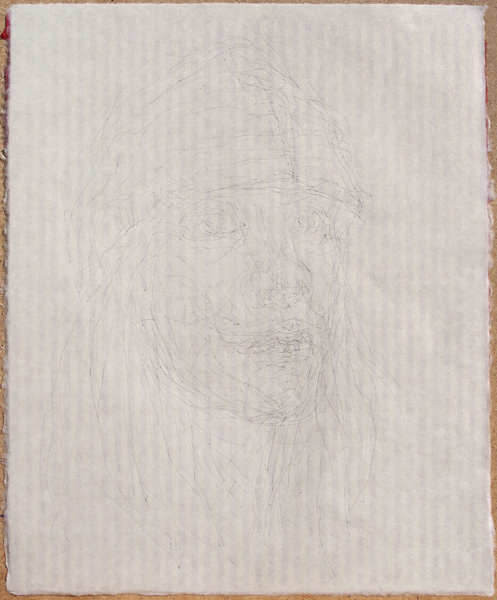

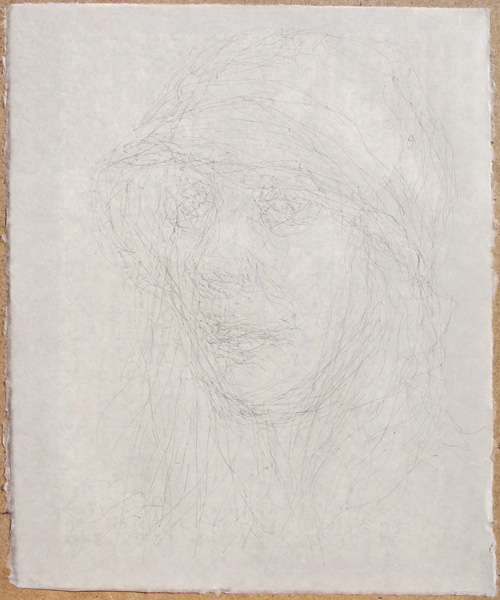

In her new series, "Masks and hats", Maria Kazanskaya "wanted to make

it funny" just like Chagall did: just as he turned his forest this way

and that, so Maria wanted the same face to appear each time on a

different background, in a different medium, now with a long nose, now

with a short one, now in a scarf, now in a hat---the funnier the

better. The artist's face is her favorite toy, a set of make-believe

armies always in the midst of battle. Maria has fearlessly sacrificed

her face to her own hunger for meaning and liberation.

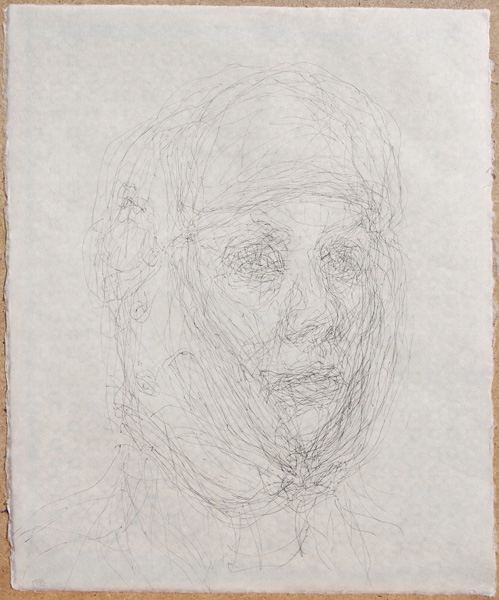

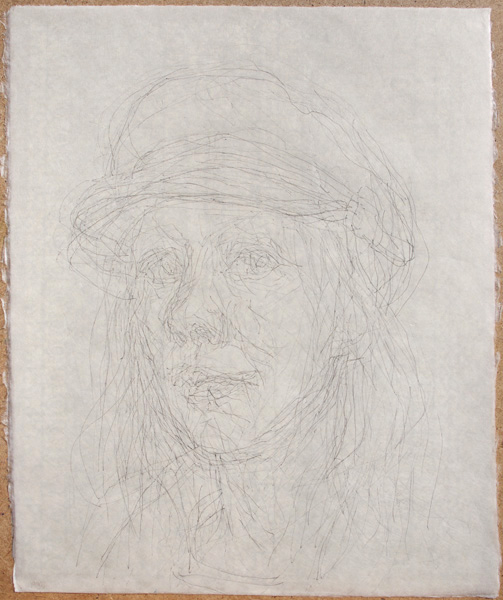

This series has some initial uncertainty, instability in its hurtling,

thin, frightened lines. There's some brittleness, broken monologues,

quotations from "Flowers", a series of paintings in which flowers are

more individual than people. There are serene glimpses of nature,

which must be Maria's sister---that's how familially she paints water

and rocks, trees and sand; though in "Masks" the trees are

superimposed, netlike, on her face, the water sparkles here and there

in her eyes. And in culmination, self-assured chords of color,

punctuated by screams about the pointlessness of all our efforts.

Paintings are located in space; they speak of space. It's harder to

speak about time, though many things have been said about it by many

people. It seems like the whole world draws, paints, designs websites

and apartments. All China and many elsewhere sew beautiful dresses.

The Library of Congress stores tens of millions of books.

But talent, real talent is still rare.

Maria Kazanskaya is one of a select few.

This is an artist's thoroughly honest look at herself, time and space.

Time, here, means life, as lived up until the very minute of the

Masks' creation. Just as a poem is the shortest path traversed by a

thought or feeling, so these masks, visual poems, are the most

condensed way of recounting time, of developing the artist's thoughts

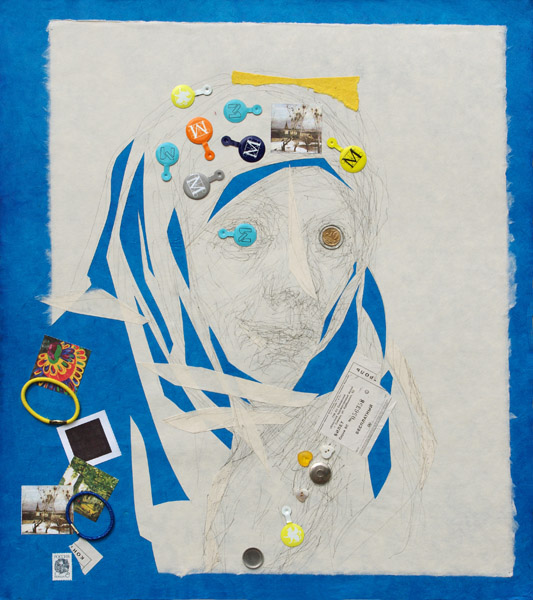

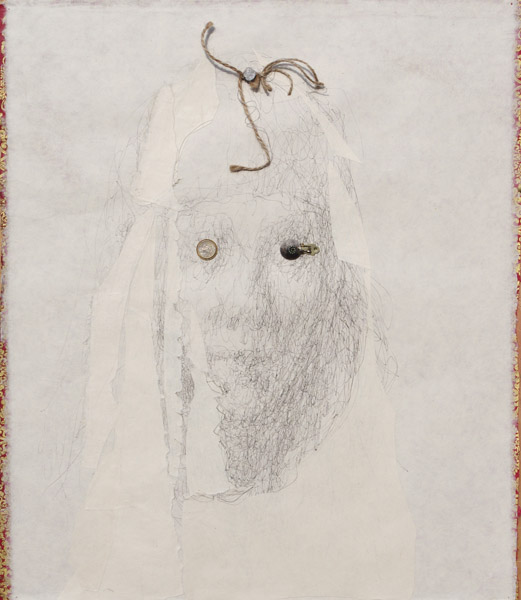

about it. Surrounding the face, you see out-of-circulation banknotes,

coins, tickets, buttons from forgotten possessions. A button speaks

about something lost, about the impermanence of things and of those

who wear them. Soviet money, which can no longer buy anything, speaks

of the unique experiences of the survivors of global cataclysms:

revolution, collapse, migrations of individuals and nations.

Dislocations, relocations, transformations of familiar spaces.

Space, for Maria, is the same kind of question without an answer, an

open wound, a rupture with Russia, with the world as she understood it

in her youth. A world in which there existed a constant friction with

her surroundings, a must for any artist; an agonizing society turned

into a fertile creative environment. Separated from her homeland, the

artist is robbed to a degree of her vitality.

But there is also the joy of being a stranger. In a foreign land, in

foreignness, you can hide, forget, get away from yourself, and find

yourself anew.

The joy of foreignness is just as bright as its bitterness is bitter.

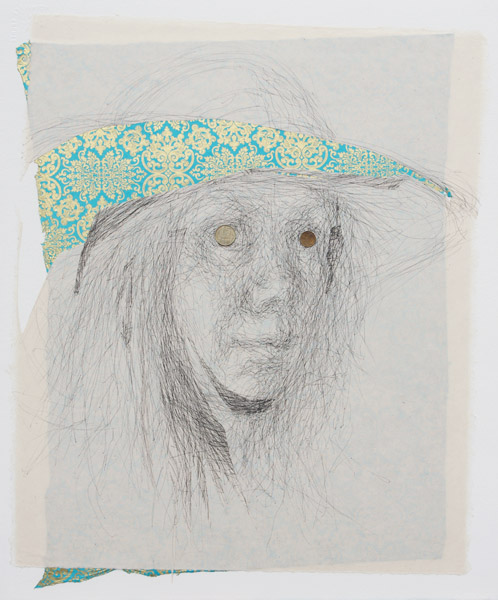

The joy of the Japanese paper that flaunts the face so festively; the

joy of a new land, the discoverer's joy of blue and yellow, water and

sun, shading that same face. The joy of an overseas vacation, of a

yellow hat, dark sunglasses---with a patch of polka dots, a childhood

memory: the sea, a bucket, the sand, a tiny dress. And all of a

sudden, amidst the torn fragments of colorful paper, on the same face

there's a thread, some foreign stamps, a bottle cap from imported

beer. "In a black glass bottle from imported beer..." This song

sounded comfortable in a familiar, predictable world, where we weren't

responsible for anything; the cap hangs on its thread fearsomely, like

a scab torn from the face, a cap from an utterly, irreversibly foreign

bottle.

Somewhere is a place whose flesh we are torn out of, like buttons

hanging on the thread of fate.

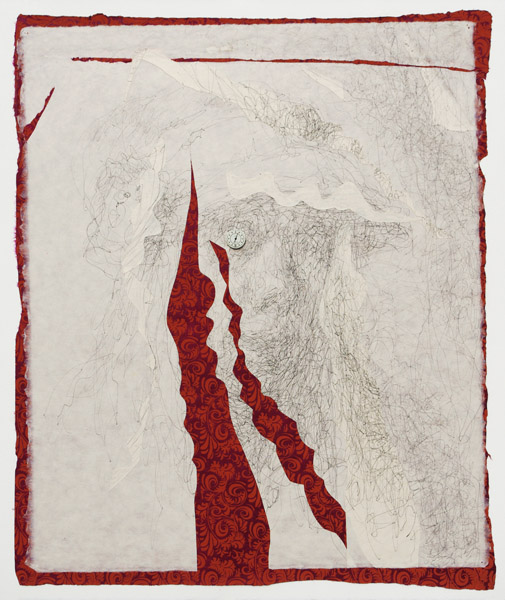

Time and history don't end with the cataclysms of the last decades in

Russia or even all of Russian history. In a pencil self-portrait with

a wrapped-up face, we discern Rembrandt with a bandaged face, a face

which was always so unsettling when it stared from the page or from a

museum wall: is he sick? Is he deaf? Sick, deaf, lost: no true

artist has a cloudless biography, they're all wrapped up in shreds of

their fractured lives, ruptured time, disintegrating space.

So other masks disintegrate, sprawl apart: black and white, with

bewilderment and fear in their wide-open eyes. Another millimeter,

and these eyes will burst open, dripping; their radiance will turn to

tears.

Colors don't clear up the essence here, they muddle it. They change

the face until it's barely recognizable, surrounding it with more and

more distant associations. Azure eyes? Bright red cheeks and lips?

Golden hair? It's saccharine in an almost Renoiresque way, as if

dripping with venom. What is this: a quotation in the postmodern

manner? A deconstructivist's dry laugh? No, she's simply trying to

look in that particular way at herself, and thus also at time and

space, as seen right now. And another face, a sharp oval over a

thousand thin lines: the pencil drawings of the old masters, with

their soft, noble lines, suddenly gone over with a marker.

"Masks and Hats" is an unexpected turn in Maria Kazanskaya's art. As

a painter she's restless; it's not in her nature to find a single

device, a straight path to walk along calmly, perfecting the details.

After a dramatic turn like this, it would be hard to go back to the

idyllic series of portraits of her little son Nikita, of trees, water

and rocks, in which the harmony or anxieties of the world are

portrayed precisely, but not with blood, not with a wriggling lure on

a hook. How can you go back when your face is hooked, held prisoner

by hats, jerky lines, streaks and explosions of color? It doesn't

have anywhere left to hide. It burns and ripples, reflects and is

reflected. It's hard to imagine such a self-portrait in a Carmel

gallery. It's even harder to understand one of them without looking

at the others, because this new series of Maria Kazanskaya's works

speaks also about the way time distorts our guises, about the way

space multplies them, and about the way that the face nevertheless

remains, in any guise, itself.

[show less]

By Julia Nemirovskaya, translated by F. Manin